The year is 250 BC. King Ptolemy II wants a copy of the Jewish law for his new library in Alexandria. Seventy-two Jewish elders (six from each of the twelve tribes) travel from Jerusalem. After seventy-two days, they produce a Greek translation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible.

Depending on which version of the story you hear, they were also locked in seventy-two different rooms. And (of course) each of them produced exactly the same translation at the end.

This translation came to be known as the Translation of the Seventy – a number pretty close to seventy-two, I guess. "Septuagint" comes from the Latin word for "seventy." It's also abbreviated with the Roman numeral for seventy: LXX.

Of course, these are just legends. In reality, we know very little about the origin of the Septuagint. But it may be the most important Bible translation ever made.

The History of the Septuagint

Traditionally, the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) was written over a millennium, beginning with Moses (13th–15th century BC) and possibly not being completed until the 2nd century BC. As the name suggests, it was written in Hebrew. But after Alexander the Great (d. 323 BC) conquered the known world, many Jewish communities began speaking Greek as their primary language. This created a demand for a Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures.

The translation of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible) probably did appear in Alexandria sometime in the 3rd century BC. Most likely, different people translated each of the five books. But we don't know who they were.

The rest of the Hebrew Bible followed after that. As with the Pentateuch, the translators remain unknown. While the translation of the Pentateuch was of high quality, the quality of the rest of the translations varied. The translators also varied in their translation philosophies, as we'll discuss below.

This translation – the Septuagint – became the received Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible during the time of Jesus and the apostles. As a result, the New Testament often quotes from the Septuagint. In fact, some of the best manuscripts of the Septuagint that we have are from Greek Bibles that contain both the Old and New Testaments!

The spread of the Jewish scriptures in Greek also helps explain why so many foreigners (such as Cornelius and the Ethiopian eunuch) were ready to convert to Christianity. They already knew the Hebrew Bible – in Greek!

But the widespread Christian adoption of the Septuagint didn't sit well with Jewish people who didn't convert. So, in the 2nd century AD, three new Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible appeared. Aquila of Sinope produced a very literal translation. Symmachus produced a more dynamic translation (but still "essentially literal," comparable to the ESV). Theodotion was somewhere in between. Little is known about any of these three Jewish translators. But they're often called "The Three" (in contrast to The Seventy).

The final stage of the Septuagint's evolution comes with the Christian scholar Origen (d. 253). Origen prepared a massive polyglot Bible called the "Hexapla" (Greek for "sixfold"). This Bible had six columns: Hebrew, a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew, the Septuagint, and each of the Three. Origen then corrected the Septuagint against the Hebrew, sometimes supplementing with Theodotion when the Septuagint left stuff out.

The Hexapla was probably lost during an invasion of Caesarea in 638 AD. But many of our oldest Septuagint manuscripts include the changes that Origen made.

The Contents of the Septuagint

The Septuagint contains all 39 books in the Protestant canon of the Old Testament. But it is also the source of some additional books that are in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox canons. In Protestant circles, these are called "apocryphal" or "deuterocanonical." These are: Tobit, Judith, Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah, Sirach, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and the Wisdom of Solomon.

The Eastern Orthodox also accept a few more books found in the Septuagint: the Prayer of Manasseh, 1 and 2 Esdras, and 3 and 4 Maccabees. Some Septuagint manuscripts include other books as well, such as the Psalms of Solomon. All of these contain additional historical narratives, sayings, and poetry composed after the exile but before the New Testament.

In addition to these "apocryphal" books, the Greek translations of Esther and Daniel contain additional material. Greek Esther contains accounts of Mordecai's apocalyptic dreams. Greek Daniel contains more stories about Daniel's exploits as a young man, and the song that his friends sang in the fiery furnace. There's also a 151st psalm, allegedly written by David after he killed Goliath!

The Greek versions of Exodus, Proverbs, and Jeremiah have some parts which are out of order. Other books – Job, Jeremiah, and Daniel – are significantly shorter in the Greek. Some books are translated literally (such as Ecclesiastes), others dynamically (such as Daniel). The differences in ordering and length could be due to these different translation philosophies. But it could also be that sometimes the translators were working with different Hebrew texts.

The Usefulness of the Septuagint

The original, intended use of the Septuagint is lost to history. But some scholars think that it was originally intended for "interlinear" use – that is, to be read alongside the Hebrew in an educational (rather than liturgical) context.

Whatever its original usefulness was, there are two ways the Septuagint is useful to us today.

Text Criticism

First of all, it is a witness to early versions of the books of the Hebrew Bible. Yes, the Hebrew Bible was written in Hebrew. But the oldest complete Hebrew manuscripts we have date from the 10th century AD and beyond. Yes, you read that right – AD – which means many of the manuscripts we have are over a thousand years newer than the original texts. On the other hand, the oldest complete Septuagint manuscripts we have date from the 4th century AD. This makes the Septuagint a valuable piece of the puzzle as we try to determine what the earliest form of the biblical text was.

Sometimes it seems plausible that the Septuagint preserves things that were accidentally left out of the later Hebrew manuscripts. For example, in Genesis 4:8, the Hebrew says that Cain "said to Abel his brother." Said what? The Hebrew doesn't finish the sentence. The ESV translates this as "spoke to Abel" to make it sound more natural. But the Septuagint and many other ancient translations relate that Cain said, "Let us go out to the field."

If this was present in earlier Hebrew manuscripts, it may have been left out by a scribe whose eye skipped a few words as he was copying. In this case, it is plausible that that happened. So much so that many modern translations include Cain's words, either in the main text or footnotes.

This process of looking at the available manuscripts and determining which is closer to the original is called text criticism. But we won't get into the details here. I recommend chapter 2 of Scribes and Scripture for an accessible introduction.

The problem is that the Septuagint is not reliably better than the Hebrew manuscripts we have. That's why all (Protestant and Catholic) English translations prioritize the Hebrew as the most reliable witness to the original text. But translators today still consult the Septuagint, and you can find references to it in the footnotes of your Bible. Start by checking Genesis 4:8!

New Testament Theology

The Septuagint is also useful because it helps us understand the origins of New Testament theology better. For example, why does Paul say that Jesus "became sin" in 2 Corinthians 5:21?

For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God. (ESV)

In Greek, the word for "sin" just means sin. But in Hebrew the same word can mean "sin" or "an offering for sin." The Septuagint translators just translated the word woodenly as "sin" for both of these. This probably reflected an existing practice in the Greek-speaking Jewish community (a phenomenon known as "calquing"). Paul here might be expressing that Jesus became a sin offering for us. But because he is writing in Greek he borrows a calque from the Septuagint.

Here's one more example. In John 10, Jesus defends himself from the charge of blasphemy by appealing to the Hebrew Bible.

Jesus answered them, "Is it not written in your Law, 'I said, you are gods'? If he called them gods to whom the word of God came – and Scripture cannot be broken – do you say of him whom the Father consecrated and sent into the world, 'You are blaspheming,' because I said, 'I am the Son of God'?" (John 10:34–36, ESV)

Jesus is here quoting from Psalm 82:

God has taken his place in the divine council;

in the midst of the gods he holds judgment:

"How long will you judge unjustly

and show partiality to the wicked?"

[...]

I said, "You are gods,

sons of the Most High, all of you;

nevertheless, like men you shall die,

and fall like any prince." (Psalm 82:1–2, 6–7, ESV)

Now, it seems as though this psalm is talking about the supremacy of "God" (Hebrew Elohim) over other, lesser "gods" – perhaps the deities ruling over foreign nations. But Jesus reads it as talking about the rulers of the people of Israel ("those to whom the word of God came"). What's going on here?

As it turns out, Jesus is appealing to a tradition in the Judaism of his time which sometimes reads "Elohim" as referring to human judges. The Septuagint preserves this tradition elsewhere, for example in Exodus 22. Exodus 22:28 in the Hebrew reads:

You shall not revile God [Elohim], or curse a leader of your people. (NRSV)

Which is ambiguous – "Elohim" could mean either "God" or "gods." Most English translations go with "God." But in the Septuagint it gets translated:

You shall not revile gods, and you shall not speak ill of your people’s rulers. (NETS)

This treats "gods" as a synonym for "your people's rulers." So, Jesus' interpretation of Psalm 82 didn't come out of the blue. Rather, it would already have been well-known within his community.

Sometimes the Septuagint also informs the New Testament's specifically messianic theology as well. For example, in Isaiah 7:14, the Hebrew talks about a "young woman" – the word could mean "virgin" but has a broader range – giving birth. The Septuagint translates this using a word that has the more narrow meaning of "virgin." Matthew picks up on this to explain Jesus' miraculous conception:

Now the birth of Jesus Christ took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit. [...] All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet: "Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Immanuel" (which means, God with us). (Matthew 1:18, 22, ESV)

But in other places, the Septuagint actually obscures things that the New Testament authors take to be messianic prophecies. When John describes Jesus being crucified, he says:

For these things took place that the Scripture might be fulfilled: "Not one of his bones will be broken." And again another Scripture says, "They will look on him whom they have pierced." (John 19:36–37, ESV)

That second citation is a quote from Zechariah 12:10, which in the Hebrew reads:

And I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of grace and pleas for mercy, so that, when they look on me, on him whom they have pierced, they shall mourn for him, as one mourns for an only child, and weep bitterly over him, as one weeps over a firstborn. (ESV)

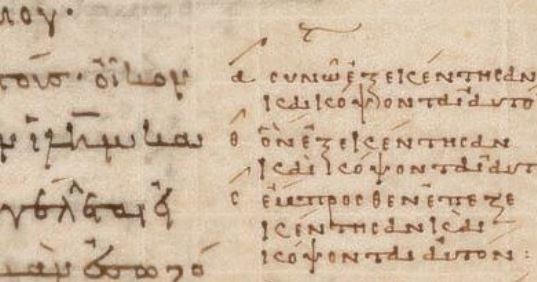

But the Septuagint looks very different:

And I will pour out a spirit of grace and compassion on the house of David and on the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and they shall look to me because they have danced triumphantly, and they shall mourn for him with a mourning as for a loved one, and they shall be pained with pain as for a firstborn. (NETS)

So, John is quoting either from his own translation, or from another existing translation – perhaps a precursor to Theodotion's.

Read for Yourself

Today, you have several options for reading the Septuagint in English. The modern scholarly translation is the New English Translation of the Septuagint (PDFs are available at the link). Lexham Press also now has its own translation, available through Logos or in hardcover. Charles van der Pool, an independent scholar has produced an interlinear Greek-English edition, which you can read online at BibleHub. He continues to produce regular videos going through the Bible in Greek and English on his YouTube channel. Finally, the Old Testament in the Orthodox Study Bible is a version of the New King James Version that has been brought in line with the Septuagint.

Older editions include Sir Lancelot C. L. Brenton's 1844 translation, which can be found in many places online. This is the gold standard of public domain translations. But since high school, I have also been working off and on to produce a better digital edition of Charles Thomson's 1808 translation – which was both the first translation of the Septuagint into English, and the first English Bible translation done in the Americas. Perhaps I'll get around to finishing that project someday.

Read more about Metapolis supplements here.

Posts that reference this supplement: